Our empirical grasp of reality grows increasingly malleable as virtual and augmented realities proliferate alongside generative technologies like GANs, NERFs, and Gaussian splatting. Powerful AI systems can now synthesize stunningly realistic media, causing the boundaries between real and simulated to blur. Amidst this turbulence, the singularity of human conscious experience remains our anchor.

Autoethnography offers a methodology to ground these multiplying technological layers with vulnerable subjective storytelling. Blending autobiography and cultural analysis, autoethnography illuminates how societal forces shape personal realities through first-hand accounts. The researcher is both subject and instrument.

By privileging intimate narratives, autoethnography upholds the value of our irreplicable lived experiences. As AI proliferation threatens to engulf authentic human connection, personal storytelling sustains our footing amidst these virtual frontiers. Autoethnography provides ballast against dehumanizing tendencies, celebrating those ineffable qualities fundamental to conscious life.

Moreover, autoethnography can serve as an antidote that also enriches emerging technologies. Deeply human storytelling brings nuance and heart to what AI cannot replicate – the essence of subjective experience pursuing meaning, illuminating through first-hand accounts the human spirit that technology aims to augment but cannot replace.

Autoethnography: Weaving Personal Narratives

Autoethnography interweaves autobiographical storytelling and cultural analysis, elucidating how realities intertwine personal experiences with communal forces (Besio, 2009). This introspective methodology disrupts conventional power dynamics by situating the researcher as the subject, giving voice to marginalized people. By providing space for vulnerable self-disclosure, autoethnography highlights those qualities that make life meaningful beyond mere efficiency or objective truth.

From A Certain Point of View

Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy proposes that existence comprises ephemeral experiential events rather than static objects (Whitehead, 1929). Though perceiving continuity, our world perpetually fluctuates. Whitehead’s conceptual abstractions provide a means of articulating the relational networks shaping reality.

Donald Hoffman contends that consciousness constructs fitness-optimized perceptual “interfaces” rather than accurately depicting reality (Hoffman, 2019). Our senses present not objective truth but biological utility crafted by natural selection. Hoffman proposes layered realities, with conscious agents occupying the surface above unconscious generative processes.

Lifelogging the Quantified Self: Merging Virtual and Physical

Emerging augmented reality (AR) technologies like Snap Spectacles and Ray-Ban Stories are intermingling the physical and virtual, overlaying digital information onto real-world environments (Warren, 2021; Hodge, 2022). While consumer AR adoption remains early, its exponential development compels reflection on how these tools shape comprehension of place and culture.

The “quantified self” movement and lifelogging practices that use wearables and devices to automatically track experiences intersect with new modes of digitally logging lived experiences, potentially enriching recollection but risking the reduction of existence’s meaning to mere computable data points if applied without thoughtfulness.

Meanwhile, augmented virtuality tools like Passthrough on Meta Quest headsets enable seeing physical surroundings within VR. These categories blur as technology fuses realities across the mixed reality spectrum. While opening new creative possibilities, ethical vigilance around data privacy, informed consent, and psychological impacts remain vital.

Complementing these trends, technologies like 3D LiDAR scanning and even volumetric video captured on pocket-sized smartphones are emerging. Alongside these, 3D rendering techniques such as Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs) (Mildenhall et al., 2020), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Gaussian Spattering (Müller et al., 2022) are pointing toward the ability to reconstruct physical reality from abstract latent spaces. These algorithms create increasingly photorealistic renderings of the tangible world entirely from digital data. Although this technology trend is still nascent, it may eventually enable the digital replication, augmentation, and sharing of immersive environments constructed from the routine capture of physical spaces.

The Illusion of Presence in Virtual Reality

Virtual reality (VR) can alter our perception of reality, eliciting visceral responses to simulated environments despite conscious recognition of their artificiality (Slater, 2018). While VR adoption remains nascent, its capacity to blur the line between “real” and “simulated” requires us to remain judicious in incorporating such technologies and evaluating their impacts on social fabrics.

Presence-based media also holds powerful narrative capabilities, as in ‘spherical’ or ‘360-degree’ documentaries that provide panoramic environmental cultural anthropological insights unrestricted by conventional framing. By experientially inhabiting these documentaries, audiences can examine scenes from multiple angles, gaining holistic cultural understanding.

As virtual and augmented realities continue unfolding, it is crucial we remain cognizant of ethical considerations in autoethnographic work. When writing about personal experiences, other people are often implicated in our stories (Edwards, 2021). Technologies like smart glasses and spherical video introduce new complexities around consent and privacy.

Edwards (2021) highlights the importance of a relational ethic – attaining permission from those described whenever possible. This becomes challenging with retrospective accounts or public figures. Moreover, even consenting participants may not fully grasp how their depiction can impact them. Complete anonymity is not always feasible. There are rarely easy solutions to navigating these tensions.

Likewise, immersive technologies capturing environments must weigh the informed consent of bystanders versus rich person-centric data potential. We must thoughtfully balance the journaling of our experiences with careful consideration for those inadvertently exposed. Edwards suggests disguising identities where plausible and emphasizing composite narratives.

Ultimately, upholding human dignity should remain central. Our autoethnographic pursuits require constant questioning about whose stories we can share and careful use of words to convey care (Edwards, 2021). As virtual frontiers unfold, maintaining an ethical compass matters more than ever.

Embodied Virtual Travel

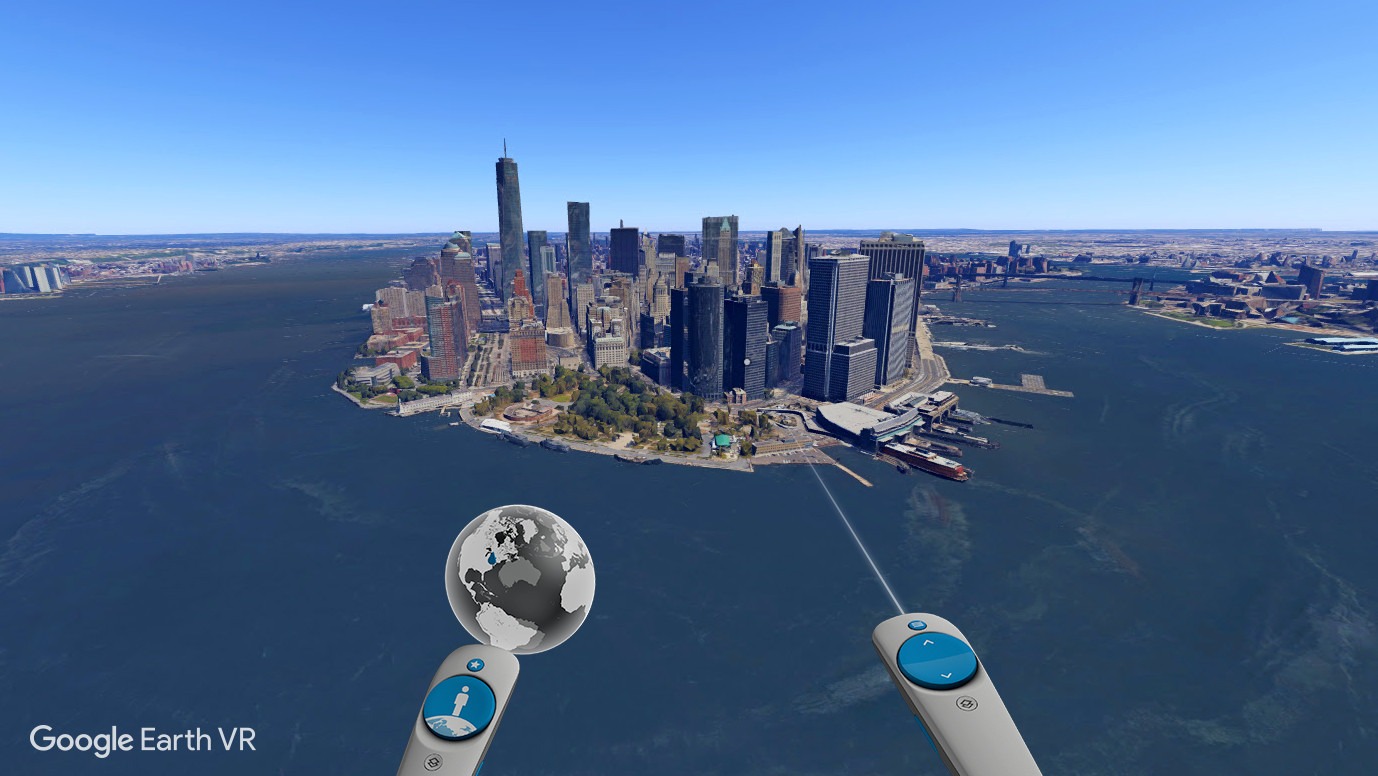

Platforms like Google Earth VR offer gateways to visit distant locales through digital embodiment. Google Earth VR suggests the potential to transform geographic education, enabling intuitive global exploration from home (Hagge, 2023). However, actual adoption still needs to be improved, hampered by technical challenges. If we can overcome these hurdles, VR’s immersive capabilities will offer students heightened spatial understanding, complementing conceptual knowledge. Moreover, it can afford participants and far more holistic perception of locales they may never get the opportunity to visit in a lifetime, humanizing the stories from afar. Nevertheless, we are squandering the opportunity, with market attention driving funding elsewhere.

I asked creator Avi Bar Zeev, co-founder and director of UX for Keyhole, which became Google Earth / Google Earth VR, about the possibility of using such volumetric geographical tools for autoethnography:

“GE (Google Earth) was always meant to be an AR world browser, like Netscape for the web, but here for geospatial data. It still can add KML (Keyhole Markup Language) files as layers. But few people ever published the equivalent of websites or general-purpose experiences.

One reason is that KML didn’t add a network effect by linking different data layers to how HTML links different sites. Another is it never got past the ‘layer” concept, where it only makes sense to have one or two layers on at a time. Full AR will need to mix and match many data sources more intelligently.

When GE merged with Google Maps, the user-generated aspect really suffered. They experimented and found people putting giant penises on their maps. And then they more or less stopped. You can make your own maps, but it’s hard to share.

From an autoethnographic perspective – everyone I’ve seen use GE or GEVR has first honed in on where they grew up. Even for VR, it’s a social experience, showing whoever is in the same room, usually on a spare screen, your origin story. ”

The adoption of virtual and augmented reality technologies has not met the expectations of many, with concerns around privacy and digital screen-related health impacts causing weariness and wariness among the public. However, it is important to recognize the tremendous utility that these technologies have demonstrated in areas such as industrial simulation and training, education, and data visualization.

The Limitations of Artificial Intelligence

Despite rapid progress, AI still struggles to capture the essence of human experience. Algorithms efficiently process data but cannot grasp life’s deeper meaning. AI falls short of representing the authenticity and spirit animating human storytelling. As Hoffman suggests, our subjective perceptions may reflect evolutionary adaptations more than objective reality. Likewise, AI risks presenting distorted renderings downstream of human phenomenology.

Navigating Multilayered Realities

Unraveling the mysteries of reality requires a thoughtful exploration of our physical, cultural, and personal experiences, which are increasingly shaped by digital information.

Evolving ideas about time and consciousness and swift technological advances are all opening our eyes to a more complex understanding of existence. Technology gives us a better view of reality as virtual and tangible become entwined. But it’s still important to take note of our own experiences, too. To move forward together, we must be courageous, compassionate, and reflective in our use of technology – always keeping human dignity and moral responsibility in mind.

Technological frontiers beckon with both promise and peril. Our journey requires a collective commitment to human dignity, empathy, and moral responsibility as guideposts to assess technological “progress.”

Heartfelt autoethnographic insights may serve as an antidote, uplifting those ineffable qualities fundamental to human life. Traveling these unfamiliar virtual frontiers requires maintaining our human anchor amidst the turbulence. Philosopher Martin Buber argued that modernity’s “eclipse of God” created a disorienting lack of moral authority (Friedman, 1955). However, rediscovering our shared human condition through vulnerable personal narratives can offer moral orientation.

By illuminating our shared hopes, fears, and pursuits of purpose, authentic personal narratives remind us that our shared humanity is the terrain that ultimately matters most. We can explore this virtual frontier with compassion and courage without losing sight of what makes us most genuinely human. Like virtual reality making the ‘natural world’ come into sharper relief for its detail, generative AI can highlight what makes homo sapiens distinct.

It is our invention, and thus, it will carry our fingerprint. Ideally, it remains our companion, and the lessons we have learned from the mismanagement of social media come into much stronger consideration as wisdom we carry forward into this irrevocable new paradigm, hoping that we remain something for machines to dream about.

References

Besio, K. (2009). Autoethnography. In Kitchin, R., & Thrift, N. (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (pp. 240–243). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00405-3

Slater, M. (2018). Immersion and the illusion of presence in virtual reality. British Journal of Psychology, 109(3), 431–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12305

Warren, T. (2021). Snap’s new Spectacles are its most ambitious yet. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/5/20/22445481/snap-spectacles-ar-augmented-reality-announced

Hodge, R. (2022). Ray-Ban Stories Review. Tom’s Guide. https://www.tomsguide.com/reviews/ray-ban-meta-smart-glasses

Hagge, P. D. (2023). The rise and stagnation of Google Earth VR: dashing the hopes of immersive geography classrooms? Geography, 108(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2023.2260222

Gefter, A. (2016). The illusion of reality. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/04/the-illusion-of-reality/479559/

Friedman, M. S. (1955). Martin Buber, the life of dialogue. Routledge.

Lindell, D. B., Martel, J. N., & Wetzstein, G. (2021, July). AutoInt: Automatic integration for fast neural volume rendering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 14556-14565).

Mildenhall, B., Srinivasan, P. P., Tancik, M., Barron, J. T., Ramamoorthi, R., & Ng, R. (2020). Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. In European Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 405–421). Springer, Cham.

Edwards, J. (2021). Ethical Autoethnography: Is it Possible? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, p. 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406921995306

You must be logged in to post a comment.